From androids to clones to babies traded to fairies, fantastic stories have a lot to say about treating people as property. Many stories examine the moral horror of owning people, its outrage to all persons’ inherent dignity. In other stories, the exchange of a person as if she is property invites audiences to consider the duties one person owes another in relationships of trust. Some of the best stories do both.

When we think of treating people as property, most of us think first and only of slavery. Enslaving people was a long, widespread historical practice that is now officially illegal worldwide. The global consensus is that enslaving people is a moral outrage, a practice incompatible with human dignity. Because of this consensus, it is easy for us to turn a blind eye to the continued practice of slavery, to imagine that, because it is hidden and illegal, it does not happen. The many portrayals of slavery in science fiction and fantasy may even reinforce the comfortable lie that slavery is a strange practice, as otherworldly (or otherwhenly) as magic and faster-than-light space travel. Sometimes critics interpret sci-fi portrayals of slavery as metaphors for other forms of oppression (e.g., The Matrix is about coming out as trans) more than as commentary on actual slavery. The newly released sci-fi novel Maverick Gambit addresses the comfortable lie about slavery in a conversation that could easily happen in our current world. When one character expresses doubt that slavery might persist despite laws against it, another character points out that making something illegal doesn’t make it go away.

Lots of sci-fi stories feature humans enslaved or otherwise owned by nonhumans. In the 1963 novel Planet of the Apes, primitive extraterrestrial humans are enslaved by intelligent apes,[i] and in the 1999 film The Matrix, humans are held captive and enslaved by robotic AIs. Not all such stories present the enslavers of humans as totally evil. Frequently they are morally complex. Still human audiences will likely sympathize with the enslaved humans and not look charitably on the enslavers and their justifications for slavery. The more strange and alien the enslavers of humanity, the more slavery is cast as not just inhuman but nonhuman. Then there are sci-fi stories in which humans own and enslave other humans. In the 2015 film Jupiter Ascending, powerful extraterrestrial humans seed planets with the components necessary for human life to develop. Then, when there are enough humans on a planet, the extraterrestrial human who owns the planet “harvests” these humans to create a youth serum, for personal use and for sale.[ii] When humans are both the enslavers and the enslaved, audiences are more likely to see slavery as an all-too-human practice, as man’s inhumanity to man.

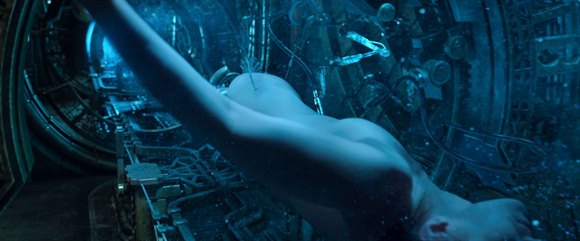

a human being harvested in Jupiter Ascending

Some sci-fi stories overtly question the humanity of those treated as property. Take the case of androids – for example, the 1976 Isaac Asimov novelette The Bicentennial Man, the 1993 novel The Positronic Man, and the 1999 film Bicentennial Man. In these stories, an android butler begins to express human characteristics such as creativity. He forms caring relationships with multiple generations of the family who own him, and various members consider him more or less a person. He replaces some of his mechanical parts with synthetic human organs, organs many humans use as replacement organs. As a court considers the question of his personhood, he decides to give up his robotic immortality and to allow himself to die after a 200-year life. His decision to die as humans do convinces the court to rule that he is a person. This story does not begin with a human and dehumanize him; rather it starts with nonhuman property and slowly humanizes it. The audience is left to decide whether and when the android becomes a person.

A clear successor to Asimov’s bicentennial man is the android Data from Star Trek: The Next Generation. In the episode “The Measure of a Man”, Data is put on trial to determine whether he is a person with a right to refuse to participate in a Starfleet experiment or whether he is Starfleet property with no such right. (This in a universe where humans are not the only species considered persons with rights.) Commander Bruce Maddox wishes to perform the experiment over Data’s objections and so claims that Data is property. He refers to Data impersonally as “it”. Although the episode features legal arguments that Data is property (that he is mechanical, that he can be disassembled, that he can be switched off), Captain Picard’s arguments for Data’s personhood (that he is sentient, intelligent, self-aware, and conscious) are portrayed as both more moral and more convincing. Picard concludes that if Maddox succeeds in having Data classified as property and if his experiment allows the creation of many androids like Data, then the Federation will own a race of slaves. Data is ruled to be a person rather than property, and Maddox finally refers to Data as “he”. This episode follows the Star Trek tradition of happy endings in which the morality of the main characters triumphs over contrary positions.

While humanizing androids requires us to overcome our prejudice against nonbiological personhood, human clones, featured regularly in science fiction, are biologically similar to other humans yet are often treated as property. The precise scientific difference between a clone and a nonclone is that a nonclone has two genetic parents while a clone has only one. But sci-fi stories often explore other differences. Most noncloned humans are conceived sexually and mature in their mothers’ wombs. Their parents are expected to love them and care about them as people. Sci-fi clones are conceived in laboratories by scientists, and they usually mature in a container other than a human womb. The scientists who create them and oversee their maturation expect the clones to serve utilitarian purposes. The scientists do not have the same love or duty of care to the clones as do parents to children, and this lack of care by the creators foretells that other people will see clones more as property than as people. Sometimes clones are engineered to be less human and more tool-like. The clone soldiers in Star Wars Episode II: Attack of the Clones have been engineered to age faster (so as to shorten their nonuseful childhoods) and to be more compliant than Jango Fett, the human from whom they are cloned. While the clone soldiers are engineered and intended for use, Jango Fett asks for and receives an unaltered clone whom he raises as his son, Boba Fett. Here we see how the parent/creator’s attitude to a clone foretells whether the clone is considered a person or property.

The difference between loving parents and cold, calculating creators holds true also for Data and the bicentennial man. The bicentennial man is constructed by a corporation that sells him and many models like him as home appliances. He therefore begins the story with everyone assuming he is property, and he must work to convince them that he has the same inherent dignity as they. Data, however, is constructed by a person, Dr. Noonien Soong, who raises Data as a son and whom Data calls “Father”. Soong gives Data his own face, as a child might inherit a parent’s features. Soong also programs Data to have human experiences such as dreams, even though dreams would serve little utilitarian purpose. In the Star Trek: TNG episode “Inheritance”, Data meets Dr. Juliana Tainer, former wife of Soong, who claims to be Data’s mother. She recounts her experiences helping Soong with Data’s early programming, such as writing a modesty subroutine so that Data would wear clothes. Although Data is certainly different from a human child, he is not mass produced as a tool. He is carefully created by a parent or parents (depending on how much credit we give to Tainer) and raised with love and respect, as a person with dignity. Perhaps because of these early experiences, Data considers himself a person and begins the series with everyone assuming he is a person. The later claim by Maddox that he is property is put to rest in the course of one episode.

In all of these examples, the androids and clones are out in the open for all to see, at least after they are fully grown/constructed. The question of whether they are people or property is a public question, which society either addresses judicially (Data and the bicentennial man) or weirdly doesn’t consider (the clones in Star Wars).[iii] For someone who wants to treat clones as property without the risk of disapproval and interference from society, a good strategy is to keep your activities hidden. That is what happens in the 1979 film Parts: The Clonus Horror, the 1996 novel Spares, and the 2005 film The Island. In these stories, wealthy and powerful people have themselves cloned and keep the clones to be used as tissue donors if needed, even if that means killing the clones. This practice may or may not be legal, but the clones live out of the public eye in isolated communities so that society isn’t reminded of how they are treated. In Spares, the clones live in dark, damp tunnels, and many are unable to walk or talk. (You would think such treatment might compromise their bodies and their purpose as spares.) In Parts and The Island, clones live rather comfortable lives and do not know that they are clones. When a clone is needed for tissue, she is told that she has qualified to leave their community and go to an even better place. In these films, one or more clones discover the purpose of the community, escape, and try to make known to the public what is going on. They hope that public attention will lead to outcry and pressure to stop using clones as property rather than treating them as people

The issues of cloning, tissue donation, personhood, human reproduction, and parenthood come together in a difficult-to-interpret episode of Star Trek: TNG, “Up the Long Ladder”. In this episode, the crew of the Enterprise seek to help two human colonies, the Bringloidi colony, where humans reproduce sexually, and the Mariposa colony, where humans reproduce by cloning. The cloning began because only five original Mariposa colonists survived, not enough for a sufficiently broad gene pool. The five survivors were scientists who decided to reproduce by cloning. After three hundred years of cloning themselves and suppressing sexual appetites, the Mariposans no longer feel sexual desire. However, they cannot successfully clone many more generations, because of replicative fading. Every instance of cloning introduces minor flaws into the DNA, and those flaws build up each generation. Future clones may not survive. The Mariposans ask the Enterprise crew to donate DNA that can be used to make more clones to keep their colony from dying.

Although the Enterprise crew treat the Mariposans as people and do not explicitly condemn their method of reproduction, the episode invites the audience to be critical of cloning for reproduction. Not only is there the problem of replicative fading that makes successive generations nonviable. There is also the attitude of the Enterprise crew toward being cloned. Commander Riker states that he values his uniqueness too much to allow himself to be cloned,[iv] and Captain Picard says that the rest of the crew likely feel the same. The beloved main characters thus model the critical attitude that cloning diminishes the person cloned (though not necessarily diminishing the personhood of the clone). One wonders what they would have said if asked whether genetically identical twins lack Riker’s invaluable uniqueness. I suspect that there is more to the Enterprise crew’s reluctance to be cloned than valuing one’s unique DNA. There is also squeamishness about asexual human reproduction.

The episode sets up a clear contrast between Mariposans and Bringloidi. Mariposans are technologically advanced, neat and tidy, polite and refined, calm and ordered. When Enterprise crewmembers visit the colony, they see lots of white walls and stark, minimalist interiors. Also, as mentioned, the Mariposans do not have sex or feel sexual desire. The Bringloidi colony, in contrast, is agrarian, with only pre-industrial technology. They arrive on the Enterprise as dirty and unkempt as you might expect farmers to be, and one of the first to arrive is visibly pregnant. The colony leader asks Lieutenant Worf for alcohol and quickly gets drunk. The colony leader’s daughter seduces Commander Riker, and she shouts her disapproval at Worf for having provided her father with intoxicant. The effect of the contrast is that the Bringloidi are energetic, fertile, undisciplined, in touch with nature and natural human appetites, while the Mariposans are cold, sterile, disciplined, and dependent on technology. The contrast is not entirely to the Mariposans’ detriment, but it is largely so.

The episode ends with a solution to the Mariposans’ problem with reproduction. The Mariposans agree to reproduce sexually with the Bringloidi at least until they have a broad enough gene pool. The Mariposans’ first reaction to this proposal is disgust, as one might expect given their lack of sexual desire. This disgust at an activity most humans engage in makes them less likeable to the audience and less like the main characters on the show. But there is also a commonality with the main characters. When the Bringloidi insist on bringing their farm animals aboard the Enterprise, Picard is highly annoyed. Not only are the animals messy and in the way; their use as food also conflicts with nutritional practices and morals on the Enterprise. In the episode “Lonely among Us”, Riker informs an alien species, “We no longer enslave animals for food purposes”. The meat 24th-century Federation humans eat does not come from living animals but is synthesized in a replicator.[v] Riker’s term “enslave” characterizes eating animals as immoral. And when the Federation denies membership to the aliens Riker addresses, it suggests that eating animals is not in keeping with Federation standards.[vi] Picard is arguably as disgusted by the Bringloidi’s eating animals as the Mariposans are by having sex. Both of these disgust reactions are enabled by technology that makes natural human activity unnecessary. Picard, however, is not required to eat killed animals with the Bringloidi, but the Mariposans are required to overcome what we could call their sexual orientation.

While the Enterprise crew consistently treat the Mariposans as people, at the dramatic climax of the episode, two of them decide to kill two clones as if the clones’ lives belong to them. After the Enterprise crew refuse to be cloned, Mariposans surreptitiously take DNA samples from Riker and Dr. Pulaski. Once Pulaski discovers what has happened, she and Riker seek out and find new clones of themselves. The clones appear to be fully grown adults. They are lying down, eyes closed, in sealed containers. It is not clear whether they are able to survive outside of the containers or whether they have consciousness. Riker shoots the clone of himself with his phaser, looks at Pulaski, receives a nod from her, and shoots the clone of her.

The Mariposan leader accuses Riker of murder, because he considers these new clones to be people. But Riker seems to consider that because the clone was made from his tissue without his permission, he has as much to say about what happens to the clone as he does about what happens to his own body. He seeks Pulaski’s permission to destroy the clone of her, as if he believes she has the same rights to the clone of her that he has to the clone of himself. Picard appears to share the idea that Riker and Pulaski own the products of their DNA. He asks a Mariposan, “And that gave you the right to assault us? To rob us [. . .]?”. It makes sense that taking tissue from someone’s body without her permission would be assault. To call it robbery is thought-provoking. Do we own our bodily tissue, at least the tissue that we haven’t shed or discarded? If so, do we own what someone produces from that tissue, even if what is produced is a person?

I do not know whether the writers of this episode were thinking about abortion, but the parallels to abortion are striking. Riker and Pulaski have genetic offspring that they do not want. The offspring are sealed off from the environment as if in artificial wombs. Although we can see their faces, they appear to be asleep or in stasis, eyes closed, expressions neutral, so that we cannot tell whether they are sentient or aware. If allowed to mature, they will certainly be people like the Mariposans. Whether they are yet people at the moment Riker kills them is the question.

Unlike what would be the case in sexual reproduction, these clones do not gestate in the bodies of Riker and Pulaski. They are not physical burdens to Riker and Pulaski. Riker and Pulaski would, arguably, have no duty to support and raise them. (What family structures, if any, are there are among the Mariposans?) The only ways the Mariposans have imposed on Riker and Pulaski are 1) by “robbing” them of some bodily tissue they would not miss, 2) by compromising their genetic distinctiveness, as Riker stated, and 3) by taking from them the decision of whether to reproduce and to care for their offspring. The third seems to me most important, but it doesn’t come up explicitly in the episode. To find this concern, the concern that one might unwillingly have offspring to whom one might owe a duty of care one cannot or wishes not to perform, we have to read it into the facial expressions and nonverbal cues of Riker and Pulaski. Do they feel a parental right and duty to care for their unconventional offspring? Would they rather kill their offspring than allow their offspring to live estranged from them, among the Mariposans? Or, as Riker indicates, do they only feel degraded by having been cloned?

The sci-fi stories discussed here focus mostly on who counts as a

person, with relationships between parent/creator and offspring/creation as a

lesser concern. Part 2 will focus on

fantasy stories where treating people as property has less to do with

questionable personhood and more to do with duties of care in relationships of

trust.

[i] The subsequent film version changes the story so that the enslaved humans and intelligent apes are on Earth, descended from the intelligent humans and less intelligent apes on Earth today.

[ii] The term “harvest” comes up also when the main character, a terrestrial human, decides to sell her eggs for money. Unfertilized eggs are hardly human beings, but some would consider selling them an affront to human dignity. Using the same term for selling eggs as for owning and harvesting human beings invites a comparison. Is it wrong not only to own humans but also to own and sell the tissue capable of making humans?

[iii] It is strange that the Republic doesn’t rule on the personhood status of the clones given that enslavement of sentient species is illegal in the Republic. Slaves like Anakin are held in the Outer Rim where the Republic has little power. However, since the Republic commissioned the creation of the clone army, in a sense buying them, and since it benefits from their labor, the Republic has significant motivation to avoid legally determining the clones are sentient persons with the right to refuse to fight. This interpretation suggests that the Republic is not only bureaucratically bloated but also corrupt.

[iv] In a much later episode, “Second Chances”, Will Riker discovers that he is not genetically unique. When he was transported from planet to ship years earlier, the beam split so that one Riker materialized on the ship and another back on the planet. There are two genetically identical Rikers. The Riker who materialized on the planet, not the Riker of the Enterprise, is not featured in any other episode of The Next Generation, and thus Will Riker’s uniqueness as a character is protected. The second Riker does appear in one episode of Deep Space Nine, where he impersonates the Enterprise Riker in order to commit an act of terrorism.

[v] However, in the episode “Family”, Picard visits his brother and sister-in-law on Earth, and we see that they do not use a replicator but cook food from scratch. Whether they cook meat is not specified.

[vi] Vulcans, members of the Federation along with most humans, are vegetarian.